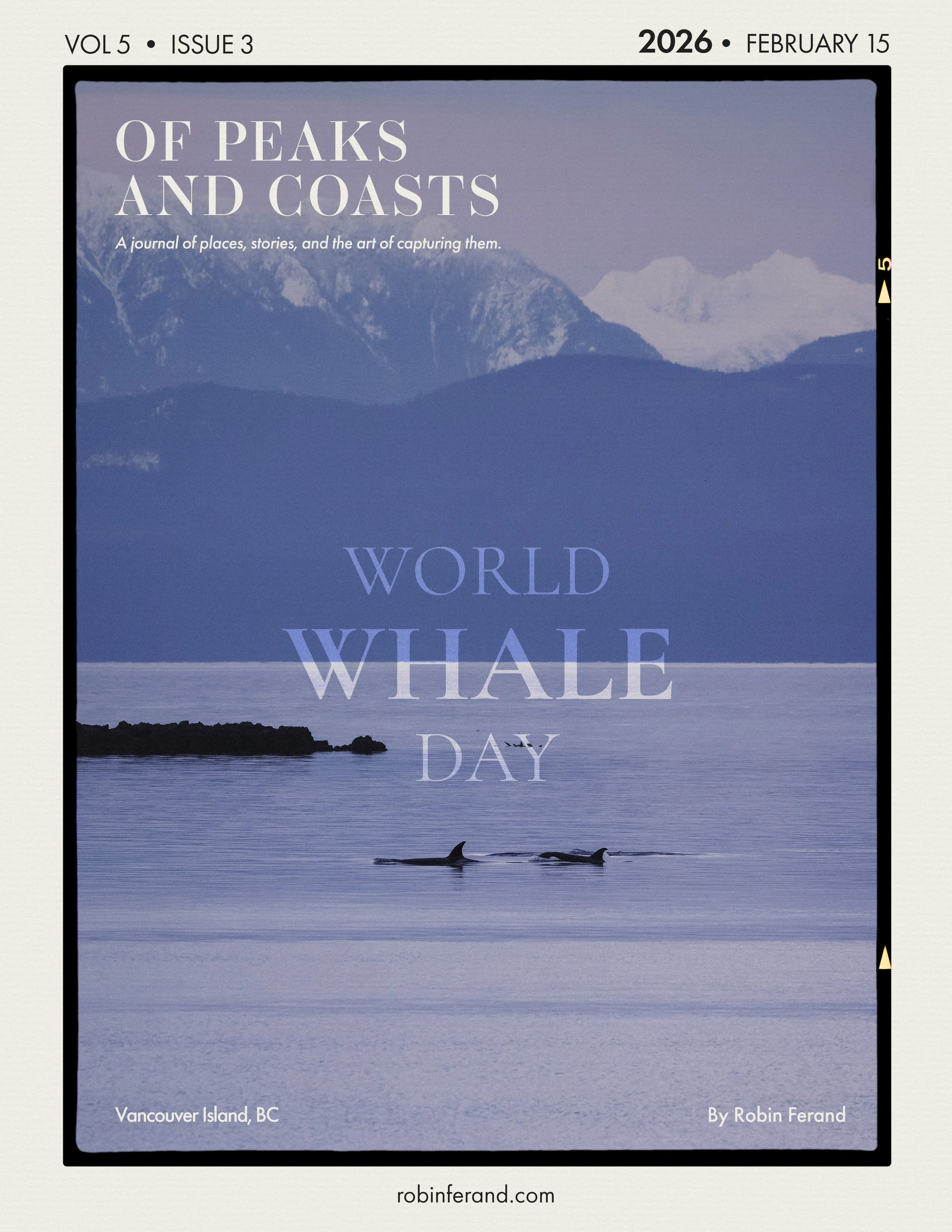

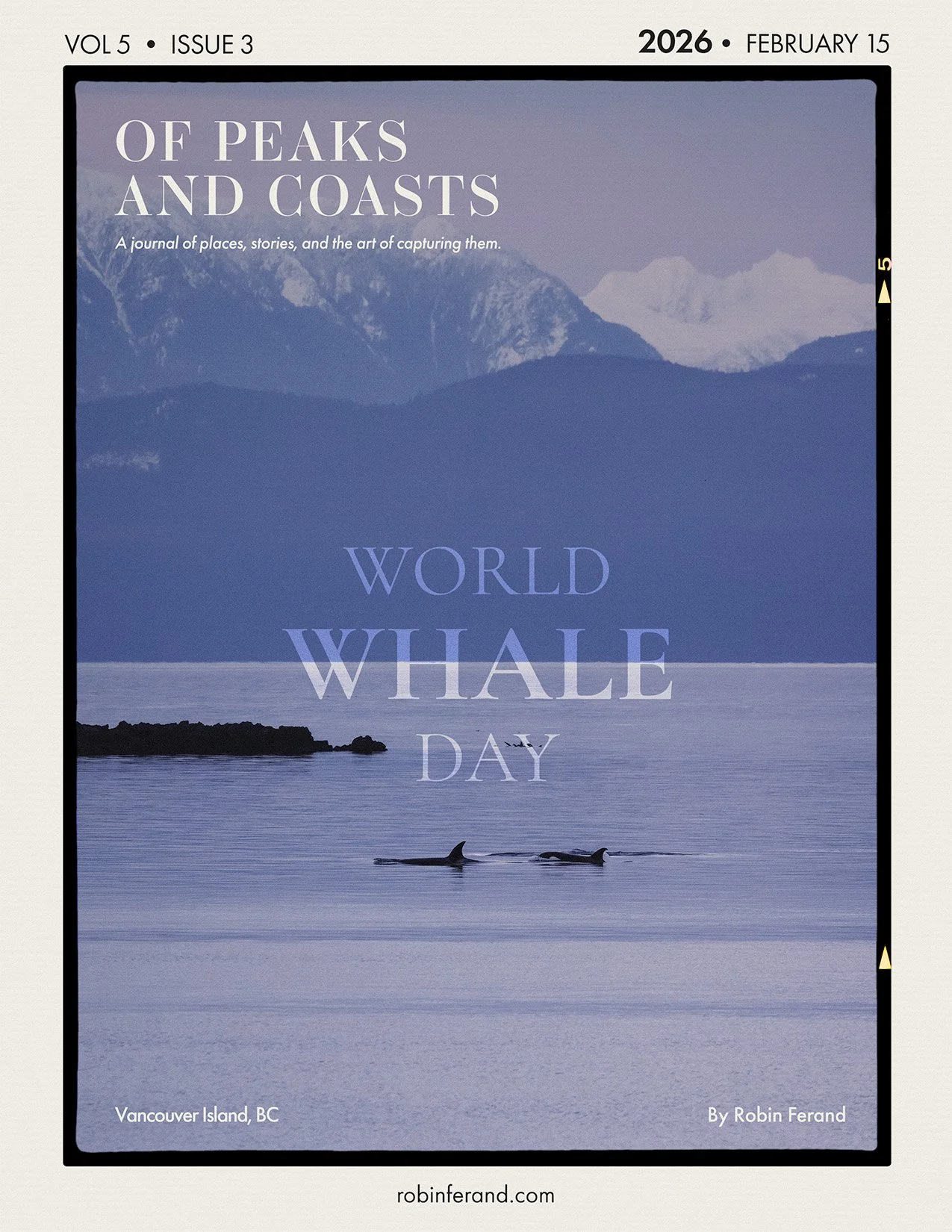

World Whale Day

W

hen people ask why I moved to Vancouver Island, I say, “For the whales.” It is the simplest answer. It is also the truest. But I am not a marine biologist, no job brought me here. It began the way many things begin. With a story I loved as a kid.

I grew up in the nineties, when there was no Online Netflix, only VHS tapes, some bootlegged, some bought. And like many I was in awe when I watched Free Willy for the first time and believed, the way children believe, that the ocean was a stage where the good ending always arrives. I still have the plush my mother bought me back then. It is worn now, but it is still here.

As a child, I also went to the marine park in the south of France. I watched orcas perform their tricks. I did not know what I was watching. I did not know what it cost them. Later, I learned that the real spectacle was never in the concrete tank. It was the open water. It was the animal choosing its own direction.

Twelve or so years later, it was aboard a whale watching vessel off the coast of Washington State that the Wild taught me my first lesson: Nature does not answer a trainer’s whistle.

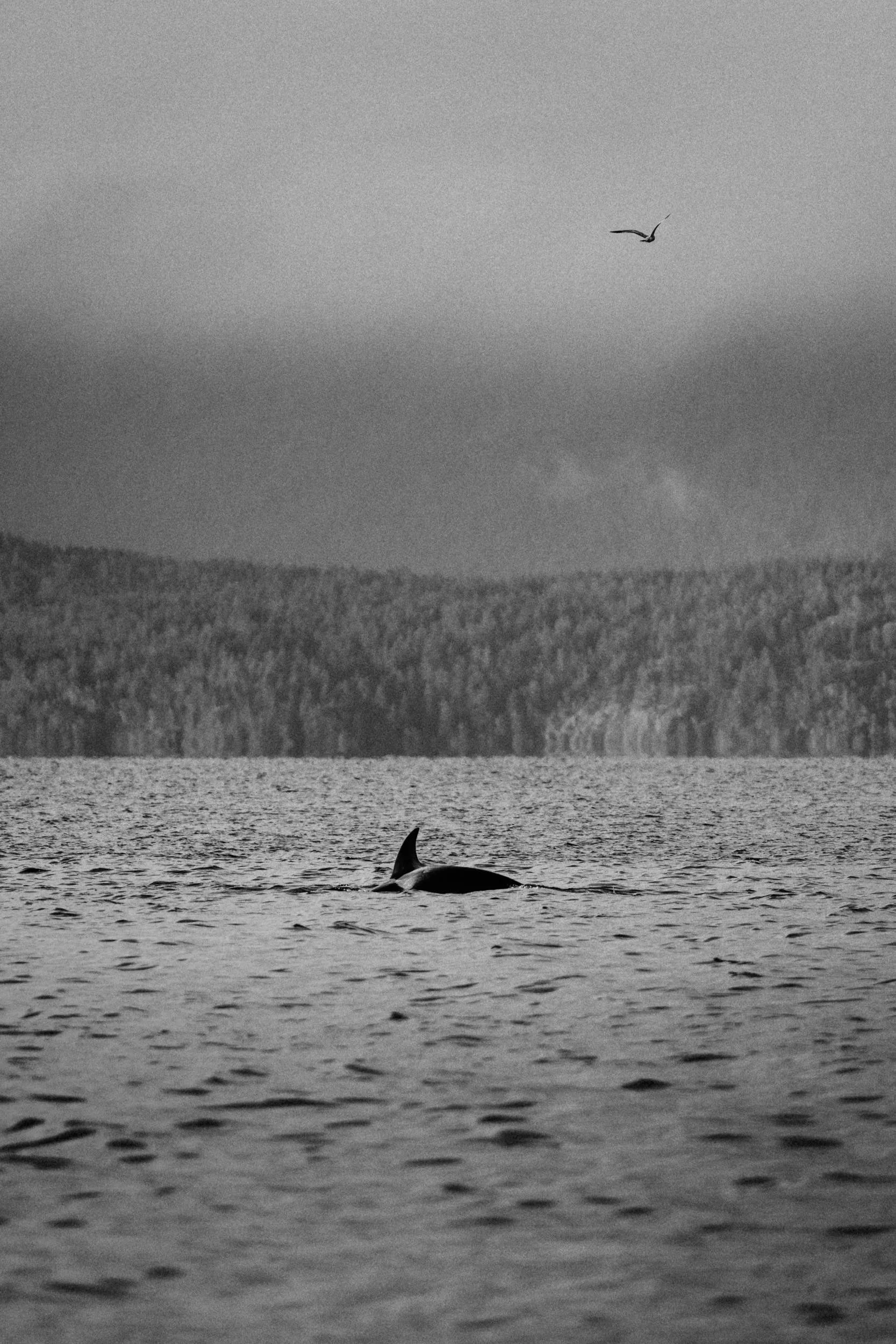

You cannot stand on the coast of the Salish Sea and expect a Hollywood epilogue where the Southern Resident orcas rise on cue in Puget Sound on a Michael Jackson’s track. You cannot show up with a camera and demand the ending you came for simply because you dreamt of it for many years. The sea is not a set. So you wait. You learn where to stand. You learn how to look. You learn the tides and seasons. More importantly, you become part of a quiet community of people who care enough to keep coming back and share live sightings so that more can partake in the chase that never ends, even when it often results with an empty horizon. But over time you start to read what is in front of you. A flock of birds, a commotion in the water, a distant blow like breath on cold glass. You begin to understand patterns and behaviours, not as certainty, but as clues. You get better odds, but you do not get guarantees because wild animals are what makes them wild, unpredictable and secretive.

We have studied whales for decades, and we still know so little. We may never know enough to feel satisfied. That is fine. Because that not-knowing is part of the devotion. If we knew everything there was to know about whales, we might stop paying attention. We might stop protecting them. Canada, like many countries, carries a dark history in these waters. Whales were hunted, killed or captured. They were treated as resources, then as entertainment. And yet Canada was also one of the first places to shut down the whaling industry and push toward protection, sanctuaries, and research.

People may ask why transient killer whales, ranging from Alaska to California, are sometimes called Bigg’s orcas. It is because of Dr. Michael Bigg, a Canadian biologist who changed how orcas were seen. Not as nuisances. Not as monsters to be shot on sight by the Navy as target practice. But as intelligent apex predators with culture and social structure. He helped start the practice of identifying individuals, learning pods, assigning IDs, and later names. Much of that work still shapes how we understand them today.

But it is not all about orcas. Vancouver Island sits in rich water. In late winter, grey whales pass through. Sometimes you hear of a minke, or a fin whale farther out. And most often, you find the beloved humpback. Humpbacks were brought to the brink of extinction. Then protections held. Now they are thriving again in these waters, to the point where, if you know where to look, they can almost become a common sight. Almost.

Most of my sightings have been from shore. On the water with a wildlife tour you can get better angles, better shots and more of the animal. But there is something unique about meeting a whale from land. On a boat, you are in their element. You travel over their routes, scanning the strait and, looking for them in the middle of their world. On shore, it is different. When a whale comes close, it feels like a shared space, briefly borrowed by us and them. And while the whale did not come for you, I cannot shake the feeling of meaning in that closeness.

After centuries of chasing them for blubber, after harpoons and blood and smoke, we stand there now with binoculars and telephoto lenses, still seeking them, still chasing them, but for a different reason. What makes us stands hours on the shores under a sharp wind, devoted to a potential sighting?

I remember one encounter from the beginning of the year, somewhere around Nanoose. Between December and January, several humpbacks stayed near shore to feed instead of pushing farther southwest toward Hawaii, the way they often do. They gave an incredible show, especially for people in Lantzville that for many felt like a blessing during the Holiday Season.

One evening we drove to Nanoose Bay where we saw five or six humpbacks scattered in small groups. Some close. Some far. The day was ending and a winter wind numbed our fingers and ears. The tide was higher than usual and stole the rocky shores. Nanoose Bay has a particular shape. On the eastern side, the water drops deep quickly. That is why whales can swim so close to shore. I was setting my camera on the tripod, aiming toward a group farther out, when we heard a loud swoosh to our left. Then another. It was close. Really close. We turned and there, maybe fifteen metres away, was a massive dark-grey back, spotted and slick and you could see the blowhole and the greenish barnacles along the skin. The whale dove along the underwater cliff, and for a moment, the closeness of it all made it looked like it was swimming right beneath us. Nor Ellanna nor I lifted a phone. No one reached for the camera either. We did not even think of it. We just stood there, frozen. Not from the cold but from a much stronger inner force. In that moment, there was no urge to document. Why hide your eyes behind a screen just to share it instantly? Why trade the real thing for proof? We stayed in the moment. The media card was replaced by a memory. Now I had seen humpbacks from boats before but I had never been that close from one. I am still amazed that something so large can fit so near the flooded edge of that place that shall stay nameless.

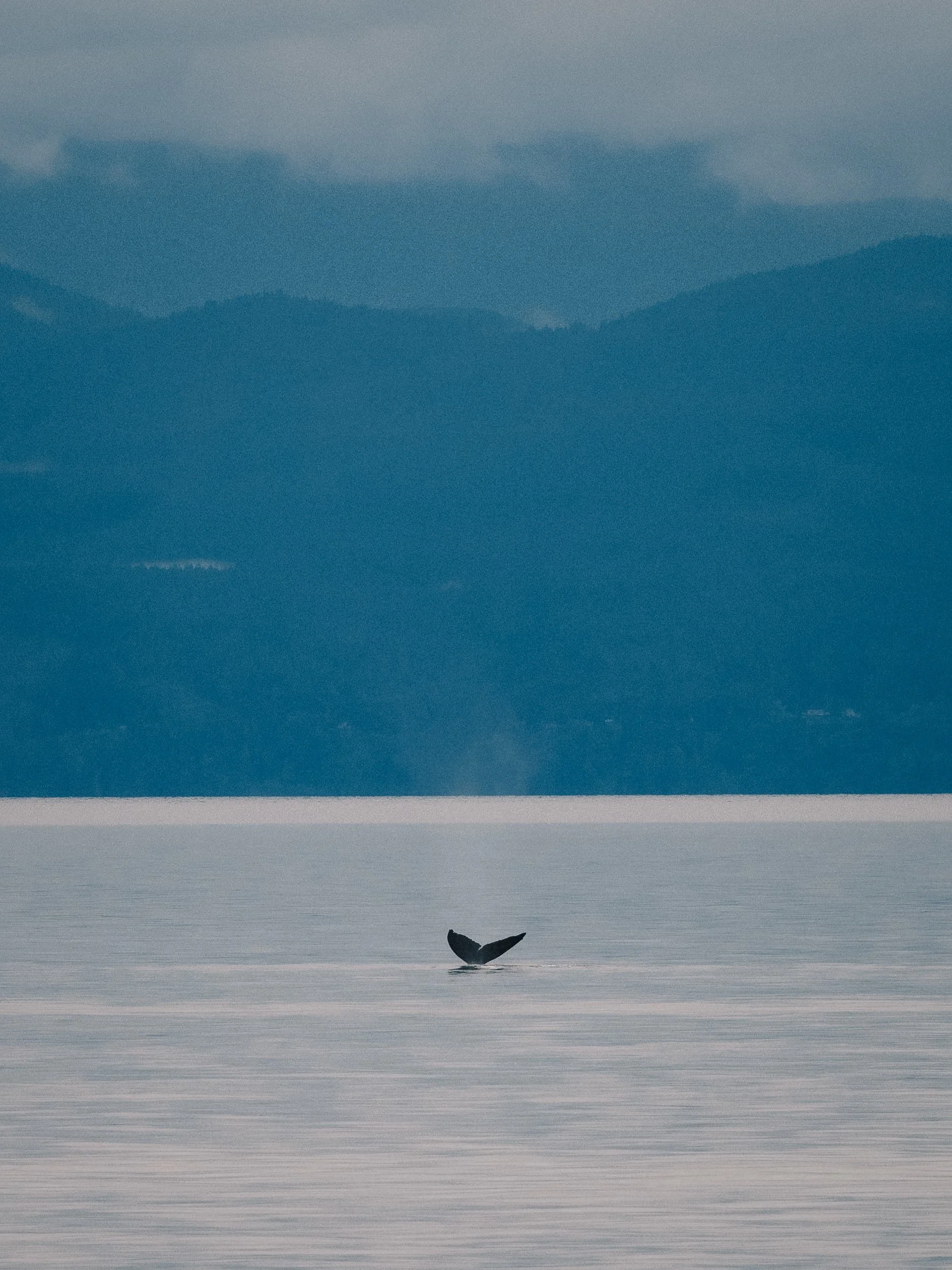

I have lived on Vancouver Island for almost four years now, and my camera bag stays ready. Some days I get only a small fluke on the horizon, half-lost between whitecaps. Another day, a pod of orcas passes so close to shore that you can feel their breath detaching from a dark tree canvas under a golden setting sun.

And still, that same question remains. Why do I keep seeking them, why do we keep seeking them? If you describe it plainly, it sounds repetitive. You drive. You walk to the water. You wait. You scan the horizon. You wait again. Sometimes you see black fins far out, or a fluke lifted high and sliding back under the waves. Often you see only ten percent of the animal’s mass. Then it is over. That was the show. It does not sound exciting on the page, does it.

Yet we will continue to do it a thousand times more. We might just never stop. It is a fascination that is hard to explain. It is one of those things you understand only by being there. Yes, the photos online are gorgeous, and you may see more of the whale in a video than you ever will with your own eyes. But being there asks something from you. Patience, attention; a willingness to leave with nothing. And when it comes, it is not just a sighting like a moose crossing the road in the distance but rather it’s an encounter. It’s a moment when you feel connected. Not the Hollywood connection of Free Willy, but connected to your surroundings, your place in it as a human and to the whale moving through it all. It might teaches you humility. It might make this place you call home even more important. More worth learning about. More worth protecting.

That is why I came here for the whales. And that is why I stay.

PHOTOGRAPHS FEATURED IN THIS POST

DISCOVER EVERYTHING I USE TO CAPTURE WILDLIFE

Disclaimer: when you purchase an item through these links, I might earn a small commission which helps supporting my work and keeping this website ad-free.

Thank you!