2025 - The Year in Pictures

EACH DECEMBER,

timelines fill with “Best of the Year” posts from photographers and filmmakers. People gather their best work, line up their numbers, and hit publish. In a world where images vanish between screenshots and receipts; that simple act matters more than you think. The simple action of selecting a few of your favourite photos and curating them to an album named Best of the Year is enough to start your personal archive, and there is no need to share if you don’t want to.

In 2019, I pushed things further. I designed a full magazine of photographs, complemented by personal stories and field notes. The plan was simple: one issue per year. The reality was not. Curating, writing and designing took time, and only one issue—2018: The Year in Pictures—made it to paper. I’m still planning to complete the rest of the years, eventually. For now, my best of the years live in Lightroom collections like small islands of order in a sea of raw files.

Aside from printing, which is the most important part, I also like to build an online presence. Until this year, I would often select my ten favourite shots of the year and publish a blog post attached to an Instagram post. And I might still do that; however, I also wanted to push things further once again. I selected twelve moments. Twelve scenes that stayed. The ones I think will be worth returning to when the memory softens, and the details start to drift.

1 - Capturing the Pacific Herring Spawn

If you are not a biologist or living on Vancouver Island, the Pacific Herring Spawn might mean nothing more than a line in a field guide. Here, it is an event that wildlife photographers and nature enthusiasts highly anticipate. Each year, between February and March, schools of Pacific herring gather along the coast to spawn in the kelp forests. Females release roe, males rush in with milt, and the cold water turns to a milky shade of emerald. It is the signal of a great wildlife gathering. From the small harbour seals to the large Steller sea lions, all feasting on the oily fish. Above, gulls and bald eagles draw looping shapes in the air, diving on scraps and leftovers. And with so many sea lions gathered, transient killer whales closely monitor the coastal waters, hunting for some that are too preoccupied by the amount of food to remember, there is always a bigger fish (in this case, a mammal).

The first time I witnessed this was in 2023, a single day of chaos with long lenses and numb fingers. For 2025, the ambition grew. The Herring Spawn became the first collaboration with photographer and filmmaker JJ Sereday. Together, we pitched the Parksville Qualicum Beach tourism board our idea: document a natural spectacle that draws more visitors and fuels local eco-tours each year.

We spent a week on the central east side of the Island, from Denman Island to Nanaimo. Some days were spent walking on white foam-covered beaches, others on boats rolling in the swell. The event itself was as frantic as it was beautiful. Birds screaming, sea lions lunging, and the water boiling with life. Out of that chaos came a handful of frames that still feel right. A small collection from a week where the ocean turned white, the air smells of sea fish, and the sky never seemed quiet.

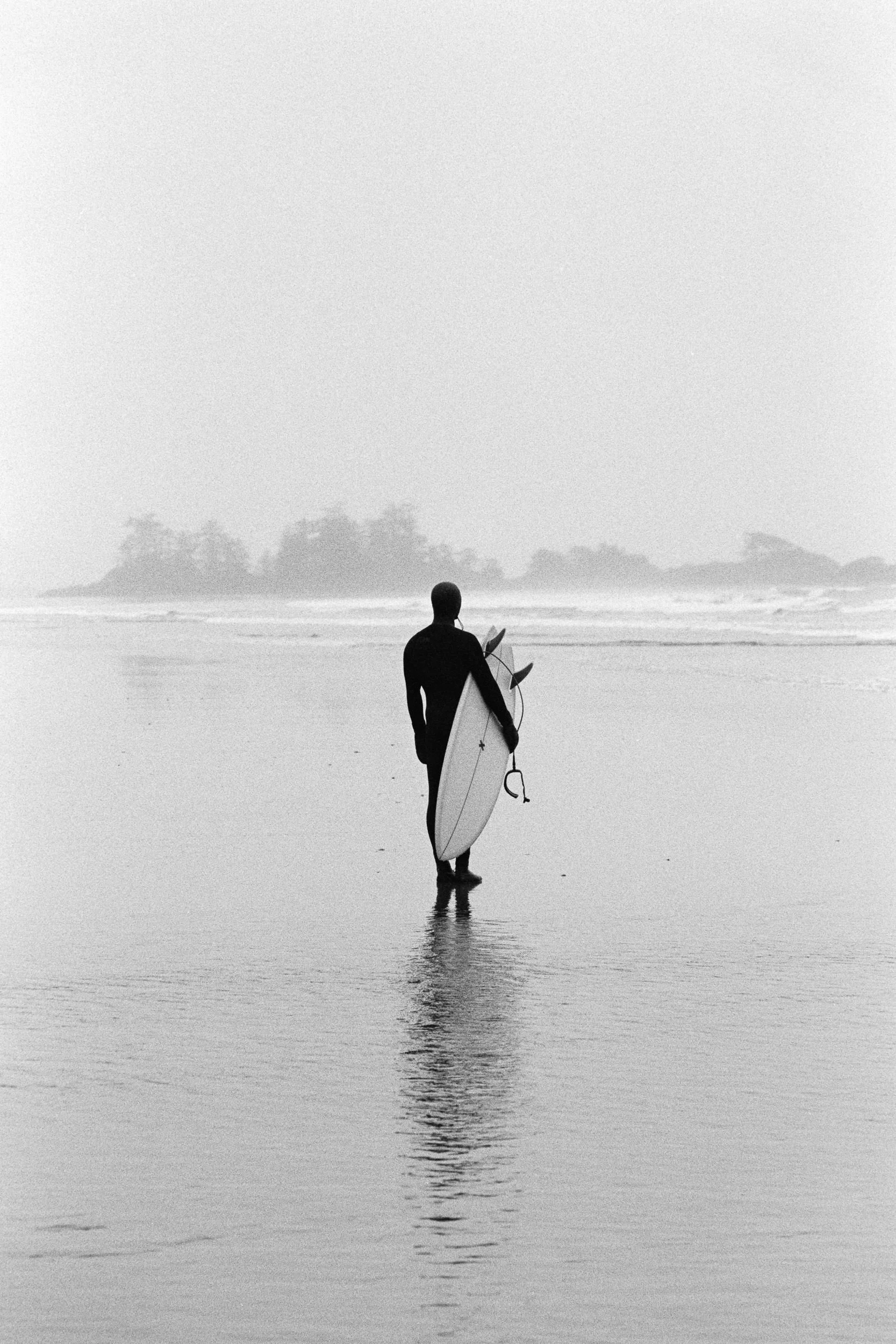

2 - A Foggy Viewfinder

Since moving to Vancouver Island, it almost become a tradition to visit the West Coast. A few days between Ucluelet and Tofino to mark our birthdays, just one day apart. It is also off-season, meaning rooms are cheaper, but the odds of rain are higher. But that trade feels fair.

I always thought that rain suited the wild coast. Storm waves slam the rocks. Fog drifts through the trees. Everything is damp, dark, and a little wild. With good waterproof clothing and a half-resilient camera, it can feel like the perfect time to shoot, at least in theory.

By day three, my Canon R5C began showing condensation in the viewfinder, and moisture crept into the lens. This came as a surprise since a week before, the same camera had survived hail during the Herring Spawn on a whale-watching boat. Looking back, I think the difference was subtle but real. The cabin we stayed in had poor ventilation, think humid heat inside, Cold and wet outside; Humidity everywhere; basically a recipe for disaster.

By day four, the camera dried out and has behaved ever since. A funny but unfair comparison; the film camera—an old Canon Elan 7—kept working throughout the trip without complaint and was also part of the Herring Spawn project. Of course, it was not recording 4K downsampled footage and high-bitrate video. Digital sensors generate heat. Add cold, wind, and constant rain, and physics takes over. In the end, the camera survived, the trip held, and the memory of that fogged viewfinder remained part of the story.

3 - An Unexpected Encounter

Living on Vancouver Island teaches you how to look for whales, if you’re into that kind of thing, of course. You learn pod patterns, you track tides and wind, but most importantly, you keep notifications turned on for the Facebook Messenger group that shares live activity on whale sightings. Over the past three years, we’ve had several close encounters with killer whales from shore. This one, however, would become unique.

On a warm April day, word came that a large pod of killer whales was travelling south from Qualicum. My camera bag always ready, it was a quick drive to Nanoose Bay. There, on the shore, binoculars on my face, I scanned the horizon for a familiar black curve against the waves. After twenty minutes, faint blows appeared far out. They grew in size and sound as the animals approached. Excitement rose with each breath.

But something felt different. Instead of travelling in small groups, with males on the edges and females and calves tucked in the middle, these whales moved in a long, parallel line across the horizon. The pattern clicked. These were Southern Resident killer whales, the J Pod, not transients. Residents feed almost exclusively on Chinook salmon and spend much of their time in Washington waters. And when they do visit this coast, they often travel farther offshore than Bigg’s (transient) whales, which cruise closer in, hunting seals and sea lions.

Seeing Southern Residents is already rare, as endangered species, whale-watching boats cannot approach them, nor can private boats. But seeing them hugging the shore felt unique, almost unreal. As the pod neared, it was time to shoot. The Canon R5C came out. The trusty EF 100–400mm followed, but something else was different; however, this time it felt wrong. The lens was shorter than usual. The EF-to-RF adapter was missing. Suddenly, I recalled that moment a few days earlier when I had used the lens with my old Canon 5D Mark II. The adapter never made it back into the bag.

There was a brief moment of disbelief. A high, silent curse. And the Killer whales were approaching. There I stood on the rock, flagship camera in hand, a long telephoto on the other, with no way to connect them. That day, wildlife photography happened with a 24–70mm lens.

What could have been a technical disaster became something else. At 70mm, composition mattered less. Despite how close the whales were, there was no reason to overthink framing; it would still be too wide. So I kept the camera at body height, low, and broadly framed toward the whales, firing almost blind, while my eyes stayed locked on the black fins. Most of my whale encounters have been through a viewfinder. This time, the encounter became less about taking images and more about seeing.

The Southern Residents are some of the most endangered orcas in the world. Fewer than 75 individuals remain across J, K, and L pods. Calves are lost to malnutrition, and their primary prey—Chinook salmon—is scarce. Knowing that, watching JPod pass by within meters of shore, even without the perfect lens, felt like witnessing something fragile and fleeting.

Read more about Southern Resident Killer Whales.

4 - Looking Up

Auroras are not typical on Vancouver Island. And when they are forecast, it often feels like a rumour until the sky proves it. The last two years, though, have brought a handful of nights where the north glowed green and purple, subtle to the naked eye, much bolder on the back screen of a camera.

In early June, forecasts pointed to an intense solar storm, with the best chance of a show between the night of the 2nd and the 3rd. The plan was to head out on the big night, June 3rd, around 22:00, with charged batteries, a roll of high-speed film, a tripod and a little bit of hope.

The evening before, word spread that weak auroras were already visible. I felt like staying put, waiting for the “real” event. Ellanna suggested going anyway. “We can always go again tomorrow,” she said. So we drove to Pipers Lagoon, where the wind was relentless. To the eye, the sky looked like a pale, hazy smear. The camera, though, told a different story. Once the shutter closed and the image appeared, ribbons of green and violet danced above Shack Islands.

It was not the wild, bright aurora you see in the Norway or Iceland travel brochures. It was softer, almost shy. Still, the experience of watching that faint glow and translating it into a bolder photograph was enough. One of those images was even later reposted by *British Columbia Magazine*.

On the following night, the “big” show never came. We drove to Nanoose Bay, waiting for the sky to get darker, but it stayed mostly dull. By the third night, it was ink-black. Moral of the story? Trust women’s instinct.

5 - A Whale of a Day

Some days, the ocean hands you a double feature. This was one of them.

The day began with more shore-based whale watching. Reports of Bigg’s killer whales moving south along the coast had me (among other familiar faces) leapfrogging from point to point between Qualicum and Nanaimo. Each stop meant waiting, scanning for blows, waiting, checking the camera’s battery, waiting, hearing blows, seeing dorsal fins for a few minutes close to shore, then, far out again, signalling to head back to the car to the next location. After leaving the southern tip of Nanoose Bay, the loose plan was to reach Neck Point in time for golden hour and, with luck, catch the pod against warm light.

Instead, the orcas vanished somewhere between Nanoose Bay and Nanaimo. No more black fins, but further in the distance, larger blows appeared. Too tall and heavy to be orcas. Soon after, a wide tail fluke lifted from the water and glided below the surface. Humpbacks! For the next two hours, several whales milled a few kilometres offshore, surfacing, diving, and breaching under the cheers of a small crowd sitting all around the rocky shores of the park.

Orcas in the afternoon. Humpbacks in the evening, this turned out to be a whale of a day!

6 - My Last Rolls of Fujifilm Superia 200

It is no secret that Fujifilm has been drifting away from film manufacturing, which always feels odd for a company with the word “film” in its name. When a Canadian store announced it had a final batch of Fujifilm Superia 200—expired since March 2025, I decided to purchase the maximum amount allowed per customer: two rolls.

For most, Superia 200 is probably just another consumer film stock biting the dust. To me, it felt like the end of a chapter in my film photography journey. It was the stock that taught me how to shoot film more than a decade ago. I used it to photograph the French countryside with my father’s first SLR, a 1973 Minolta SRT-101. The soft colours, the grain, the way it rendered blues and greens with that hint of magenta in the highlights—those characteristics shape how you remember your early pictures.

Knowing these were likely my last two rolls of Superia 200, there was no rush to burn through them in a day. Instead, I stretched over the summer, a frame here, another there. Inspired by The Last Roll Of Kodachrome with Steven McCurry, I recorded the process as well, turning it into a small personal documentary about shooting the final rolls of a classic.

Nothing quintessential came out of those negatives, and it’s fine; it wasn’t really the point. At one point, while waiting for orcas (again), someone glanced at the camera and asked, “Is that film?” “Yep”. I guess a few bursts here and there of black fins cannot hurt.

7 - Rise of the Phoenix Episode II

As Superia 200 faded out, a new stock arrived: Harman Phoenix II. The first Phoenix came in a bright orange-and-red box that matched its warm tones. Phoenix II landed in deep blue packaging, which felt like a hint—maybe cooler, more subdued colours?

I bought one roll in 35mm and one in 120. The 120 roll went into the Yashica-Mat 6x6 for a day trip between Sooke and Port Renfrew. Medium format is still relatively new to me, and I tend to forget that twelve exposures vanish quickly.

The Yashica-Mat is a beautiful tool with a stubborn streak. It belonged to my grandfather and looked nearly untouched when I found it in France. Since then, it has acquired scuffs and character. Internally, though, it can be temperamental: occasional double exposures from a half-advanced lever, light leaks along edges, little quirks that randomly reveal themselves when scanning.

When I developed the first roll of Phoenix II, it needed more work in Negative Lab Pro than expected. The colours leaned hard toward blue and purple, with the same deep saturated greens encountered on its predecessor. Trying to colour-correct a brand-new film stock is subjective, since there is no widely accepted reference yet. For the first weeks after release, nobody really knows what Phoenix II is supposed to look like.

Curiously enough, the 35mm roll shot on the Minolta SRT-101 behaved a little better. The grain was stronger, as expected, but the colours were easier to tame. Less slider work overall and more frames that felt right straight away. Whether that is due to the camera, the developer, or the format, it will take more rolls to find out. In the meantime, Phoenix II has joined the list of films to explore more deeply.

8 - A Bucket Shot

By now, you might have witnessed a recurring theme: whales are not just a passing interest. I often say that killer whales are one of the reasons I moved to Vancouver Island.

Seeing whales from shore required a few things. It means living with notifications turned on, a Facebook chat dedicated to whale sightings. Keeping a camera bag ready by the door. It also means having at least one EF-to-RF adapter in the kit at all times, just in case.

On this day, the group lit up with reports of transient orcas travelling north from Pipers Lagoon. I drove to a favourite bluff along Fillinger and waited. The wind was up. Waves wore thick white caps, which made spotting dorsal fins difficult. Still, once you catch the first blow with the naked eye, you know the show has begun.

Two bulls eventually surfaced, their tall dorsal fins cutting clean lines above the swell. A fisherman saw them too and laughed to his friend, “Orcas! No more fish for a little while.” Further along the shore, a lone kayaker bounced over the waves, unaware that a pod of apex predators was swimming only a few meters away.

After they passed, I drove to Lantzville, hoping for one last look before dark. An hour went by. Nothing. Just a few swimmers. I was about to leave when an older couple approached, eyeing the long lens. “Any whales tonight?” they asked. I told them I had followed a pod from Nanaimo but had seen nothing so far. The man, calm as anything, said, “Oh, there’s an orca.”

I turned, and there they were, surfacing again, this time only meters from the beach, near swimmers who had no idea what moved past them. Someone on the sand laughed and said, “There’s Jodie swimming near orca without even knowing it.” As the pod advanced along the beach and toward the limestone point, the low sun turned their blows into golden mist. The water glowed, and you could see the clean black curves of their bodies cutting through bands of warm light and, further away, the misty silhouette of trees on Nanoose Bay.

There were no breaches, no hunts or dramatic chases. Just fins in the water, clouds of warm mist soaring above and the realization that I had finally captured yet another bucket shot of mine.

9 - Shot on iPhone X

The personal project of revisiting older iPhones continued this year. For a trip home to France in September, the choice was the iPhone X. The goal was simple: film an entire video with it. In reality, a few shots from the DJI Action 5 Pro slipped in, but the heart of the project stayed with the phone.

Re-working with the iPhone X began in 2024, during a longer stay in France. The first version never saw the light of day. In 2025, the story started over. The iPhone X is more than just a phone from a few generations back. It was my first personal 4K camera, always in my pocket. Paired with Moment lenses, it became a tiny, flexible system that stretched what a smartphone could do at the time.

This trip covered familiar places: the south of France in Var (83) and the French Alps in Haute-Savoie (74). I shot most of the images with Halide and their lovely Process Zero, and later, edited them in Lightroom. Walking those places again with a tool that once felt revolutionary brought a strange mix of nostalgia and curiosity. It was like revisiting an old notebook full of early sketches and realizing there was more there than I remembered.

10 - Le Var on Kodak Gold 200 (South of France)

Even with the iPhone X doing most of the work in France, leaving film at home was never an option. One stock in particular feels tied to that part of the world: Kodak Gold 200. On Vancouver Island, it can be hit-or-miss. It needs strong, warm light to shine. The south of France has that in abundance.

This year, along with 35mm frames, a roll in 120 went through the Yashica-Mat and produced some of my favourite images of the year.

One stands out: the sailboat. While walking the Sentier du Littoral Est on the Giens peninsula, I came across a cluster of older sailboats pulled onto a small beach. It looked like a gathering of owners with their cherished boats. Tables were set up with food and drink. The sun was dropping. Overall, perfect conditions, you might say. However, one crucial thing was missing for these sailors at heart: wind.

Out on the water, one last sailboat inched its way toward shore. It tried to coax every breath of air, zigzagging between close haul and beam reach. On land, the composition revealed itself. A tree framed the scene perfectly. If the boat drifted into that frame, the picture would be there.

So I waited. Ten minutes in the heat, fending off mosquitoes, watching the boat inch across the bay. Eventually, it slipped into the frame. The shutter clicked as the people on the beach cheered the arrival of their final friends. On its own, the image might look simple. A sailboat, a tree, a slice of sea. For me, it has weight. It’s a testament to patience, commitment, and trust in the frame you see with your own eyes, even before you raise the camera. With a digital camera, I might have zoomed in, gone tighter, tried for a different type of shot and simply moved on. But with the Yashica-Mat and a square frame, the composition was obvious, and the only way forward was to wait.

11 - Pictures from “La-Yaute” (The French Alps)

The first weeks in the French Alps did not look like a postcard. Rain. Clouds. Mist. Then more rain. Furthermore, the family cabin was under renovation, so we stayed at a friend’s place facing the Glières Plateau, a historical stronghold of the French Resistance during WWII. Staying there for several weeks, I started to develop a morning ritual: opening the wooden shutters and watching the mountains play hide-and-seek in the fog.

But it wasn’t all rain, and we caught a few bright breaks, such as the day we explored Lac Vert, with the Mont Blanc in the distance. I had a roll of Flic Film Chrome 100 loaded into an Olympus OM-2 that once also belonged to my grandfather. Chrome 100 is essentially re-spooled Ektachrome 100, but sshhh, that’s a secret not to say too aloud in fear of Kodak taking it away from us.

Fact: Slide film is unforgiving. It demands a precise light meter. The Olympus, as it turns out, no longer have a reliable one. The resulting roll came back disappointing—poorly exposed, and very hard to rescue. So the digital frames, shot as backup at first, stepped into the light, and I edited the raws with a personal emulation of Kodak E100.

“Personal emulation” is an important distinction here. I do not claim it is a perfect match for real Ektachrome. It aims instead to match how I see that stock: with the warm tones and bold contrast of projected E100, not the cold blue cast of underexposed slides with bad scans. Presets labelled “100% accurate” for film often oversell. This one is honest about being an interpretation.

One frame from that series stands above the rest: the moon rising over a peak in the Aravis mountain chain, photographed from the end of the road above the family cabin. Using my 400mm lens compressed the scene, pulling the moon closer and making it appear bolder and heavier in the frame. Timing was also of the essence. A few seconds later, it hid again behind the clouds.

12 - Shot on iPhone 17 Pro

On September 12, while still in the south of France, the iPhone 17 Pro went on pre-order. My order went in then, fully knowing the phone wouldn’t be in my hand until I returned to Canada in early October. Now, did I experience FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) when seeing everyone the following week on release day, unboxing their bright orange phones? Not really. I had plenty of other tools to capture my surroundings.

Back on Vancouver Island, October through December became the testing ground. The question was simple: Is the iPhone 17 Pro a meaningful step up from my iPhone 13 Pro, especially for someone who uses his phone as a b-camera more than anything else?

This is not a review. I don’t think a few months are enough to declare verdicts. That being said, for the most part, it looks promising. And of the few hundred images I shot so far, there are moments when it is necessary to double-check the metadata to confirm they were indeed shot on a smartphone. That alone says something, I guess.

Final Thoughts

This wasn’t the most exciting year in terms of travel or big projects. There were no far-flung assignments or new corners of the map. But it was a good year in terms of personal growth, refining workflow, and learning new skills.

For more than a decade, I’ve been searching for my style, for the way I see light, tell stories, and frame the world around me. It’s taken time, trial, and many wrong turns. But this year, something clicked. I think I finally found it; not in a single project or image, but in the sum of small choices that now feel aligned. It’s less about what I shoot and more about how and why I do it.

The rest is refinement. The slow and deliberate work of constantly shaping something that will never be perfect. As a photographer, you learn that satisfaction is rare, and maybe it’s meant to be. Each frame teaches us something, and each mistake lays the groundwork for the next step. That restless search never really ends; it simply changes direction, so keep chiselling at that diamond that is art, one stroke at a time.

I hope you enjoy these stories; let them be a slight nudge. Start your own archive if you have not already. Books, magazines, printed albums, blog posts, videos, it does not matter what medium you choose. What matters is that you pick a few images from the stream and give them a place to live.

As we shift into yet another year, the world feels even more uncertain than before, and the news rarely offers comfort. Yet art remains. Photographs, films, drawings, songs, journals, these outlast jobs, bank balances, and passing trends. People come and go. Gear breaks. But the work and the memories you create have a way of sticking around like nothing else. So keep shooting. Keep writing. Keep making.

DISCOVER MY MAIN THREE KITS

Disclaimer: when you purchase an item through these links, I might earn a small commission which helps supporting my work and keeping this website ad-free.

Thank you!