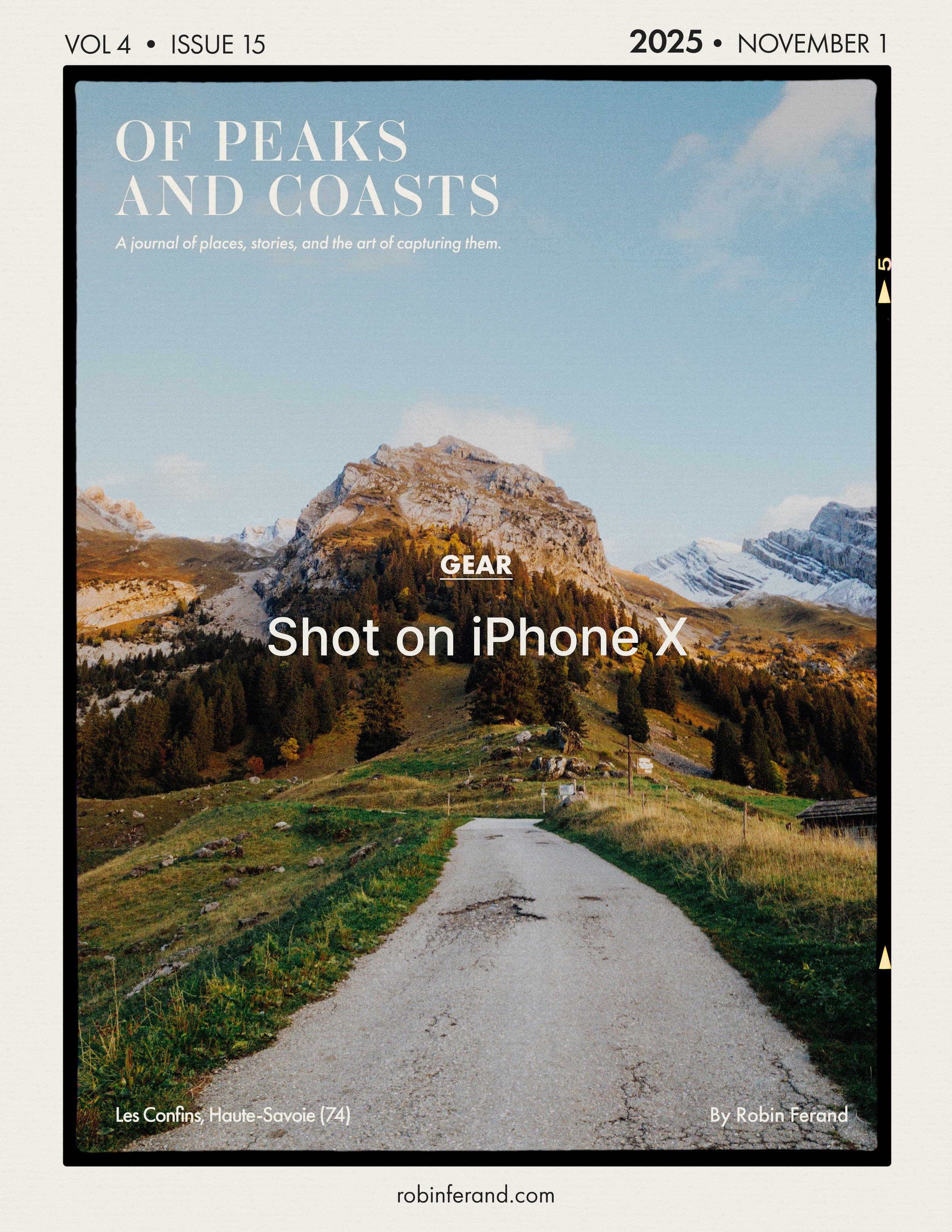

Shot on iPhone X

Revisiting the iPhone X in 2025

When the iPhone X was released in 2017, it marked a turning point in how Apple approached design and mobile imaging. It was their most ambitious redesign since the original iPhone: no home button, a stainless-steel frame, an edge-to-edge OLED display, and Face ID. It looked and felt like the future and was even introduced with the legendary “One more thing…”. Just as the original iPhone revolutionized the smartphone industry in 2007, the iPhone X in 2017 set the path for how smartphones would evolve for the next decade.

Seven years later, the iPhone X remains one of my favourite iPhones. While spending September back home in France, I decided to bring it along as a secondary camera to see how far we’ve come and how much of its magic still holds up.

Article & Video Below

Why This iPhone Mattered to Me

Although Apple leaks were not as intense back then, we knew something special was coming for the 2017 iPhone lineup. After all, it was the iPhone’s tenth anniversary. At the time, I was still using an iPhone 6, and of all my iPhones, the 6 aged the worst. You may have seen me revisit the iPhone 4S and 5S before. The next logical step would have been the iPhone 6. I tried rebooting and fully charging it, but the battery barely lasts two hours today. Moreover, I never felt that it represented much progress camera-wise. So I skipped ahead to the iPhone X, the model that truly changed things, at least for me.

In 2017, I had just started a full-time position as a photographer and videographer at a production company in Vancouver. The studio had plenty of cinema gear, but I didn’t feel comfortable borrowing it for personal projects. My primary personal camera was the legendary Canon 5D Mark II, still excellent for photography but showing its age for video.

When early rumours pointed to a major camera leap for the iPhone X, it caught my attention. I wanted a portable camera I could use every day without needing a big setup. The iPhone X seemed like the perfect personal photo and video companion. At the time, it featured Apple’s most advanced camera system yet: a 12-megapixel wide and telephoto combination capable of 4K at 60 fps and 1080p at 240 fps. In 2017, that was groundbreaking. For the first time, I could shoot 4K footage from something that fit in my pocket.

Steveston, BC - 2018 | 28mm f1/.8

Steveston, BC -2018 | 52mm f/2.4

The Two Perfect Focal Lengths

The primary camera had a 28mm full-frame equivalent focal length with an aperture of f/1.8. The second, which Apple called a telephoto, was closer to a standard lens: 52mm at f/2.4. These two focal lengths complement each other perfectly. Many street photographers rely solely on them, wide enough to tell the story and tight enough to isolate a subject. It’s also my preferred combo when shooting film, whether on my Nikon F3, Minolta, or Olympus systems.

Seeing these two lenses on the iPhone X meant I always had them in my pocket. While the 28mm is often the default choice, I found myself drawn to the 52mm more often than I expected. It didn’t perform particularly well in low light, but it never really bothered me.

Les Confins (74), 2025 | 28mm f//1.8

Les Confins (74), 2025 | 52mm f/2.4

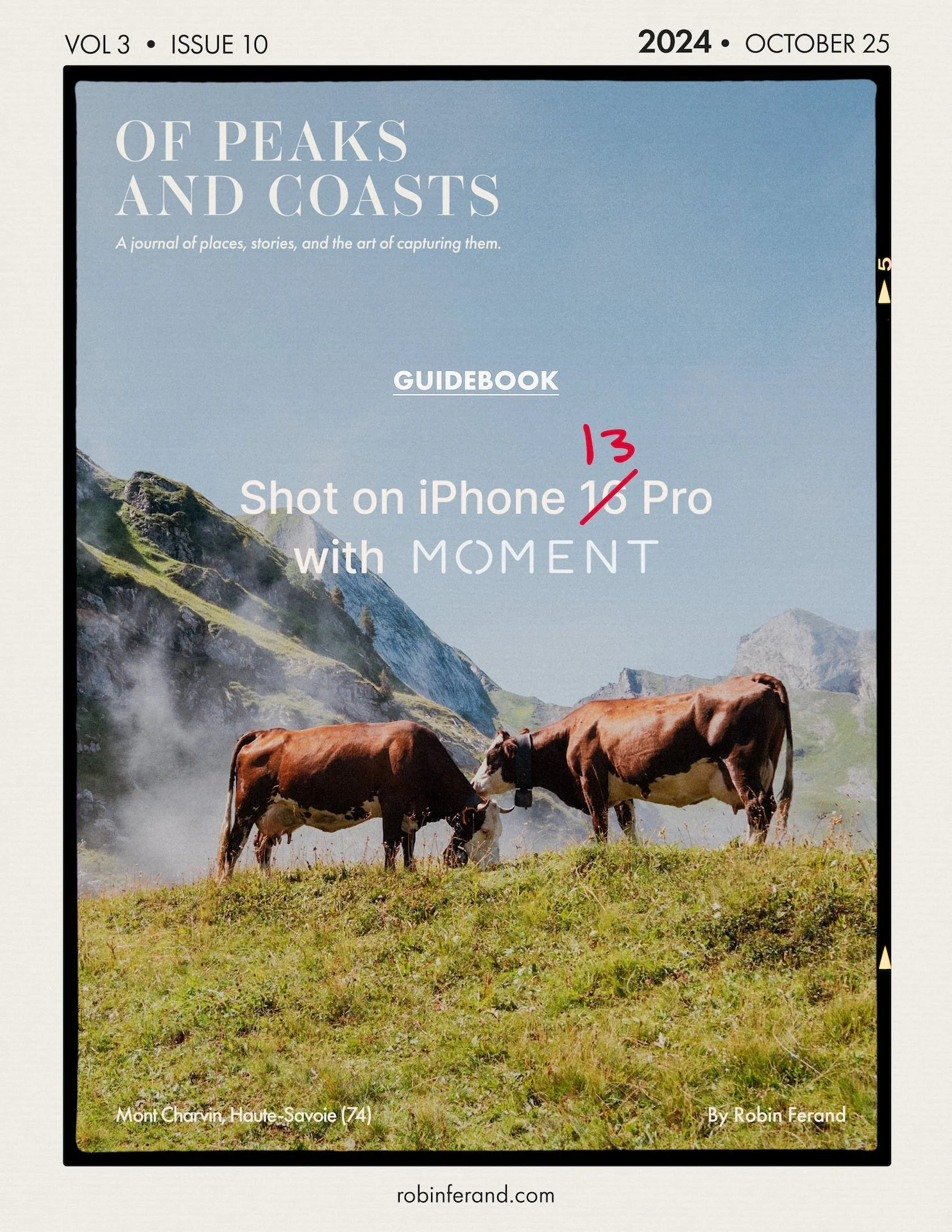

Shot on Moment

The iPhone X was also the first phone I customized with external accessories like lenses and filters. Around that time, Moment was gaining traction with a series of thoughtfully designed tools that enhanced smartphone photography and filmmaking.

It started with a phone case that allowed small, interchangeable lenses to attach directly to the body, a simple idea that opened up entirely new possibilities. Alongside my iPhone X pre-order, I ordered the Moment case with its beautiful wood back, a design they later dropped to accommodate MagSafe. I also added their 18mm wide lens. Soon, I invested more in the full Moment ecosystem, including filter holders and additional lenses. One of them was particularly exciting: an anamorphic lens. Moment launched it on Kickstarter, and I backed it. I received it sometime in 2018, and that autumn, I filmed a short road trip between Vancouver and Banff with my complete iPhone X mobile filmmaking kit. That trip has shaped how I approach mobile photography and filmmaking ever since.

Whytecliff Park, BC, 2019 | Shot on Moment Anamorphic 1.33 M-Series

Anmore, BC, 2019 | Shot on Moment Anamorphic 1.33 M-Series

Shot on iPhone X in 2025

While planning a video about the iPhone X, I thought: since it can record 4K and I still have all the accessories, why not shoot the entire project on it?

I used the Moment Anamorphic M-Series Lens, paired with the 67mm filter adapter and a PolarPro VND 2–5 stop Mist filter to control shutter speed. I couldn’t quite hit the 180-degree rule, but I came close. The mist filter helped soften the digital edge that smartphone sensors often produce. This setup transformed the iPhone X into a small, surprisingly capable cinema tool, with some caveats, of course. Audio was handled by the DJI Mic 2, delivering clean, professional sound. On the software side, I used a mix of Moment Pro Camera and the P3 app for manual exposure and colour control.

Some clips were still shot with the default camera app, just to show how the iPhone X performs straight out of the box. For shots of the phone itself and a few walking scenes, I used the DJI Action 5 Pro.

Giens (83), 2025 | 52mm f/2.4

Giens (83), 2025 | 28mm f/1.8

Giens (83), 2025 | 28mm f/1.8

The Specs Then and Now

By modern standards, it’s easy to dismiss the iPhone X. Today’s phones shoot in 8K, feature multi-lens arrays, and use sensors that can rival small mirrorless cameras. The iPhone X doesn’t have Apple Log, ProRes, or Open Gate recording. But when it arrived, 4K 60 fps was unheard of in a smartphone. So was dual optical stabilization.

Of course, the iPhone X wasn’t perfect. Dynamic range was limited, and low-light performance was modest. But it opened the door for what mobile cameras could become. More importantly, it was the first iPhone that felt like a serious creative tool rather than just a convenience.

RAW DNG

One reason I started this series about shooting with older iPhones, like the 4S and 5S, is that modern iPhones often feel over-processed. As Apple improved hardware, they also leaned heavily into computational photography: Smart HDR, tone mapping, and other algorithms that produced technically impressive but less natural results. Between the iPhone 7 and X, these features became increasingly aggressive. I remember feeling disappointed by the overly smooth look of HEIC images from the default app. Portrait Mode was fun, but for 90% of my photos, I used third-party apps to shoot in RAW DNG instead.

Indeed, since the iPhone 6S, Apple has opened the camera API to developers, letting apps access the raw data directly from the sensor. This gave photographers far more control over the look and feel of their images, especially when editing in Lightroom, Capture One or whichever software you like for that matter!

Lac Vert (74), 2025 | 52mm f/2.4

Lac Vert (74), 2025 | 52mm f/2.4

Halide and Process Zero

When I fired up my iPhone X again last year, I was surprised to see that it still received app updates. One of them came from Lux, the creators of Halide. For those unfamiliar, Halide is one of the most advanced camera apps on the App Store. It gives users full manual control over exposure, focus, and white balance, and enables RAW DNG shooting on every iPhone, not just the Pro models.

My favourite feature, added last year, is Process Zero. It’s Halide’s new RAW pipeline that produces a clean DNG file untouched by HDR or aggressive noise reduction. You can edit it later with full control or make quick, natural exposure adjustments right in the app. The resulting HEIC preview maintains the sensor’s natural grain and noise, giving it a subtle, film-like texture. You can see where highlights roll off and how the sensor renders midtones. On modern phones, those nuances are often flattened by computational processing.

Porquerolles (83), 2025 | 52mm f/2.4 | Process Zero

Giens (83), 2025 | 52mm f/2.4 | Process Zero

Porquerolles (83), 2025 | 52mm f/2.4 | Edited

Giens (83), 2025 | 52mm f/2.4 | Edited

A Proper Goodbye

The iPhone X will always be one of my favourites. Every time I take it out of the drawer, I’m still amazed by how beautiful it looks. It remains one of Apple’s best designs, sleek, balanced, and forward-thinking. It also captured a transition in technology, from home buttons to gestures, from screens with borders to immersive displays. But for me, the iPhone X represented a more personal transition, from snapshots to storytelling.

It was my first true personal video camera, and it changed the way I think about mobile filmmaking and photography. It proved that a phone could be a legitimate part of a filmmaker’s toolkit. This year, I upgraded from the iPhone 13 Pro to the iPhone 17 Pro. With features like Apple Log 2, ProRes RAW, and Open Gate, it feels more like a dedicated cinema camera than a phone. I bought it knowing it would serve as my B-camera to the Canon R5C or the Blackmagic Pocket Cinema Camera 6K Pro.

But looking back, the iPhone 17 Pro isn’t my first iPhone to fill that role. That began with the iPhone X. It wasn’t perfect —none of them are —but it was enough. It was fun. It was inspiring. And for me, that makes it unforgettable.

I’ll likely revisit the iPhone X from time to time, just as I return to an old film camera with a single roll of film. These tools are more than just devices; they illustrate the journey and history of our lives as photographers and filmmakers, showcasing the evolution of our shooting styles and subjects. Tomorrow, the iPhone 18 will capture better photos and more detailed videos, but that isn't what truly matters. Setting aside dynamic range, we end up with images that may not be scientifically perfect, yet they hold a special place in our hearts. This is because they were taken with the camera we had at that moment, not the one we dreamed of.

PHOTOGRAPHS FEATURED IN THIS POST

DISCOVER EVERYTHING I USE TO SHOOT WITH MY IPHONE 17 PRO

Disclaimer: when you purchase an item through these links, I might earn a small commission which helps supporting my work and keeping this website ad-free.

Thank you!